Why Care About Grasslands?

Immense Biodiversity

To travelers speeding along the interstate highways through the Great Plains, the impression gathered may be of much of a sameness, or of a repeated theme with slight variations, like a Phillip Glass composition. To be appreciated, Kansas grasslands require the observer to relax, take time, walk slowly, or just stand and contemplate. The varying light through the long day, the waves of wind-tossed grass, the cloud-shadows racing across the landscape, the songs of the meadowlark, Bobolink, Dickcissel, Indigo Bunting, and Grasshopper Sparrow, cannot register with the passer-by at seventy-five miles an hour. But the grasslands are a complex, varied, and unique ecosystem, with immense biodiversity spread across the middle of the continent from the Canadian Provinces through Texas, and once extending from Indiana to the Rockies. They have rightly been called “the American Serengeti.” Because the Great Plains and our state of Kansas straddle the 100th meridian, usually considered the dividing line between Eastern and Western North American species of birds, mammals, and other fauna and flora, there is great diversity of wildlife and plant life to be observed within the 400-plus miles across the state. According to the Audubon Society’s Bird-a-Thon, Kansas ranks third in the country for diversity of avian species, with some 225 species resident in season, and as many as 453 species seen at least once. The Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve near Cottonwood Falls, Kansas, reports over 500 plants, nearly 150 birds, 39 reptiles and amphibians, and 31 mammals. Researchers on the Konza Prairie south of Manhattan are uncovering a complex web of relationships between plants and animals ranging down into the prairie soil. About 600 plant species have been identified on the Konza, some sixty of them grasses. However, the grasslands are perhaps the most endangered ecosystem in the world. For example, in North America, of some 200 million acres of tallgrass prairie that once covered the center of the country, only about four per cent remains intact, most of it in the Flint Hills of Kansas. But after a century and a half of extirpation and destruction, appreciation of the unique ecosystems of North America’s grasslands is growing, to the point of the re-introduction of former keystone species such as prairie dogs and Black-Footed Ferrets, Bison, Elk, Bald Eagles, and even wolves in some scattered sites. Conservationists now understand that, particularly in grassland environments, saving postage-stamp plots of intact prairie proves inadequate; larger, contiguous stretches of diverse native prairie is essential for the territorial and foraging needs of wildlife. In many cases, ranchers have been the most diligent stewards of the land down through the years, saving large areas of grassland by carefully managed grazing and burning. And now in Kansas, we have in addition several such large preserves owned or administered by government entities or private conservation organizations: the Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve near Cottonwood Falls; the Konza Prairie south of Manhattan; the Cimarron National Grassland in the extreme southwest corner of the state.

To travelers speeding along the interstate highways through the Great Plains, the impression gathered may be of much of a sameness, or of a repeated theme with slight variations, like a Phillip Glass composition. To be appreciated, Kansas grasslands require the observer to relax, take time, walk slowly, or just stand and contemplate. The varying light through the long day, the waves of wind-tossed grass, the cloud-shadows racing across the landscape, the songs of the meadowlark, Bobolink, Dickcissel, Indigo Bunting, and Grasshopper Sparrow, cannot register with the passer-by at seventy-five miles an hour. But the grasslands are a complex, varied, and unique ecosystem, with immense biodiversity spread across the middle of the continent from the Canadian Provinces through Texas, and once extending from Indiana to the Rockies. They have rightly been called “the American Serengeti.” Because the Great Plains and our state of Kansas straddle the 100th meridian, usually considered the dividing line between Eastern and Western North American species of birds, mammals, and other fauna and flora, there is great diversity of wildlife and plant life to be observed within the 400-plus miles across the state. According to the Audubon Society’s Bird-a-Thon, Kansas ranks third in the country for diversity of avian species, with some 225 species resident in season, and as many as 453 species seen at least once. The Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve near Cottonwood Falls, Kansas, reports over 500 plants, nearly 150 birds, 39 reptiles and amphibians, and 31 mammals. Researchers on the Konza Prairie south of Manhattan are uncovering a complex web of relationships between plants and animals ranging down into the prairie soil. About 600 plant species have been identified on the Konza, some sixty of them grasses. However, the grasslands are perhaps the most endangered ecosystem in the world. For example, in North America, of some 200 million acres of tallgrass prairie that once covered the center of the country, only about four per cent remains intact, most of it in the Flint Hills of Kansas. But after a century and a half of extirpation and destruction, appreciation of the unique ecosystems of North America’s grasslands is growing, to the point of the re-introduction of former keystone species such as prairie dogs and Black-Footed Ferrets, Bison, Elk, Bald Eagles, and even wolves in some scattered sites. Conservationists now understand that, particularly in grassland environments, saving postage-stamp plots of intact prairie proves inadequate; larger, contiguous stretches of diverse native prairie is essential for the territorial and foraging needs of wildlife. In many cases, ranchers have been the most diligent stewards of the land down through the years, saving large areas of grassland by carefully managed grazing and burning. And now in Kansas, we have in addition several such large preserves owned or administered by government entities or private conservation organizations: the Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve near Cottonwood Falls; the Konza Prairie south of Manhattan; the Cimarron National Grassland in the extreme southwest corner of the state.

Prairie preserves in Kansas:

Tallgrass Prairie Preserve

https://www.nps.gov/tapr/index.htm

How the Tallgrass Prairie Preserve came to be

https://www.audubonofkansas.org/prairie-wings.cfm?fx=RZ922KOVIWPZK2J4

Konza Prairie Biological Station

https://kpbs.konza.k-state.edu/v-day/fact-sheets/history.pdf

Konza Prairie: A Tallgrass Natural History by O. J. Reichman, (University Press of Kansas, 1993)

https://kansaspress.ku.edu/978-0-7006-0450-0.html

Cimarron National Grassland

https://www.nps.gov/places/cimarron-national-grassland.htm

Audubon of Kansas Sanctuaries preserving biodiversity

The Hutton Niobrara Ranch Wildlife Sanctuary

https://www.audubonofkansas.org/prairie-wings.cfm?fx=M9828RRMQB3PGXAL

Connie Achterberg’s Wildlife-Friendly Demonstration Farm

https://www.audubonofkansas.org/prairie-wings.cfm?fx=6USGAC89SDWQYMC0

Mount Mitchell Heritage Prairie

https://www.audubonofkansas.org/newsletters.cfm?fx=ZM46S33U6X4USQUA

Birds observed at Audubon of Kansas Sanctuaries

https://www.audubonofkansas.org/prairie-wings.cfm?fx=5FU4CKSYEFY6OAG0

Articles about diverse grassland wildlife:

American Bison

https://www.audubonofkansas.org/newsletters.cfm?fx=6MEPZZWXEFDYV5KE

Black-tailed Prairie Dogs

https://www.audubonofkansas.org/conserving-black-tailed-prairie-dogs-and-associated-wildlife.cfm

Birds of Kansas: A Changing Scene

https://www.audubonofkansas.org/prairie-wings.cfm?fx=A7RZ4QJOEODG7818

Super Soil

To the pioneer farmers and homesteaders who first set eyes on the Great Plains, it must have seemed a dream come true: vast expanses of grassland uninterrupted by trees or glacially deposited boulders, with rich, deep black soil, just awaiting the plow. This quotation from 1940 exemplifies the prevailing attitude: “This is good country. All it needs is water and it will produce better than any land in the world.” (cited in Bessire, 88-89). But prairie grasses have root systems that extend many feet below the surface; they accessed and retained sub-surface moisture and held the soil bound against the erosion of wind and thunderstorm. In fact, 60% of a grassland plant’s biomass is underground. Once broken by the plow, and the native grasses and forbs were supplanted by row-crops in monocultures, thereby disrupting the system of relationships that had evolved over thousands of years; the richness of the soil became attenuated, and the fertilizers that were now required accumulated with undesirable consequences for both soil and water; no longer anchored by the root-systems of native grasses, the soil simply blew away on the prevailing winds; over-use of available water in good times accelerated the damage of drought; the monoculture of domesticated crops proved vulnerable to insect pests and proliferating plant diseases.

To the pioneer farmers and homesteaders who first set eyes on the Great Plains, it must have seemed a dream come true: vast expanses of grassland uninterrupted by trees or glacially deposited boulders, with rich, deep black soil, just awaiting the plow. This quotation from 1940 exemplifies the prevailing attitude: “This is good country. All it needs is water and it will produce better than any land in the world.” (cited in Bessire, 88-89). But prairie grasses have root systems that extend many feet below the surface; they accessed and retained sub-surface moisture and held the soil bound against the erosion of wind and thunderstorm. In fact, 60% of a grassland plant’s biomass is underground. Once broken by the plow, and the native grasses and forbs were supplanted by row-crops in monocultures, thereby disrupting the system of relationships that had evolved over thousands of years; the richness of the soil became attenuated, and the fertilizers that were now required accumulated with undesirable consequences for both soil and water; no longer anchored by the root-systems of native grasses, the soil simply blew away on the prevailing winds; over-use of available water in good times accelerated the damage of drought; the monoculture of domesticated crops proved vulnerable to insect pests and proliferating plant diseases.

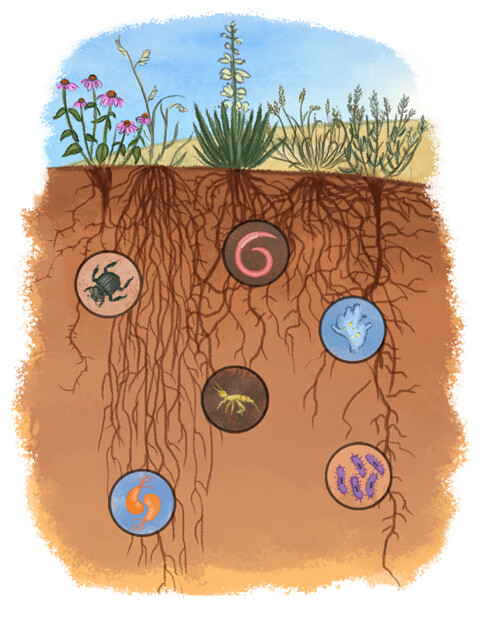

But soil is not just dirt and roots. It is a home for many grassland organisms. Some organisms, like prairie dogs and badgers, use burrows primarily for shelter. Other organisms spend all their time underground. Moles burrow underground and eat the roots of plants that they encounter. Worms digest decaying organic matter, leaving tunnels for water to penetrate the soil. Many beetles and grasshoppers find refuge in soil to overwinter. There are also multitudes of microscopic organisms living in the soil including fungus, mites, roundworms (nematodes), protists, and bacteria. These organisms include predators, fungus-feeders, and parasites. Some bacteria actually fix nitrogen by taking nitrogen from the atmosphere and turning it into a form that can be absorbed by plants. Some plants also rely on symbiotic fungi, called mycorrhizal fungi, so much that they form nodules on their roots to hold the fungus. In exchange for this ideal living environment, the fungus enhances the plant’s ability to absorb water and nutrients from the soil.

Because so much life is underground in prairie ecosystems, they are more efficient at sequestering and storing carbon than forests given the current drying and warming climate (source); in so doing, prairies are combating carbon dioxide accumulation in the atmosphere that is accelerating climate change. Standard agricultural practices do not promote carbon storage, leave the soil vulnerable to wind and water erosion, accumulate chemical poisons, and destroy beneficial fungus, bacteria, and wildlife. It is increasingly apparent that a model of sustainable agriculture must be found. And a Kansas group has been a leader in research on new and under-utilized traditional crops and sustainable methods of farming for years.

More information about organisms living in prairie soil

The Lowdown on the Prairie

https://www.chicagobotanic.org/blog/plant_science_conservation/lowdown_prairie

Microbial Life of the Prairie Fact Sheet from Konza Prairie, Manhattan, KS

http://lter.konza.ksu.edu/sites/default/files/MicrobesPrairieFact.pdf

For sustainable agricultural practices the Land Institute at Salina, Kansas, see:

The Land Institute:

https://landinstitute.org

The Land, The People, and a Proper Economy

https://landinstitute.org/video-audio/land-people-proper-economy/

The Land Institute: Civic Science Programming Lunch & Learn

https://landinstitute.org/video-audio/the-land-institute-civic-science-

On prairies as carbon sinks

Grasslands More Reliable Carbon Sink Than Trees

https://climatechange.ucdavis.edu/climate/news/grasslands-more-reliable-carbon-sink-than-trees

Traditional Knowledge

In contrast to the relations of modern industrial societies with nature, which tend to be alienated or exploitative, the ways of life of traditional native American tribal societies were more intimately integrated into their environment and shared “a deep sense of interconnectedness with the natural environment.” Immediately dependent upon the animals and plants among which they lived for all the material conditions of their life, these cultures over hundreds of years accumulated a deep knowledge and appreciation for the ways of life of the animals they hunted, and the uses of plants that could provide natural remedies for illness and injury, as well as material for tools and utensils. Increasingly, guides to wildflowers and other plants have begun to include in their descriptions notices of the uses to which native peoples put various species. Particularly in the Great Plains, the tribes have managed to retain much of this traditional lore and their sense of relationship to their environment, and government agencies and conservation organizations have found great benefits from cooperation with the tribes, drawing on their expert knowledge and immediate and reverent relation to the land in the effort to save and restore some viable portion of the rapidly diminishing, scattered remains of the once-vast, uninterrupted vista of prairie, the sea of grass.

In contrast to the relations of modern industrial societies with nature, which tend to be alienated or exploitative, the ways of life of traditional native American tribal societies were more intimately integrated into their environment and shared “a deep sense of interconnectedness with the natural environment.” Immediately dependent upon the animals and plants among which they lived for all the material conditions of their life, these cultures over hundreds of years accumulated a deep knowledge and appreciation for the ways of life of the animals they hunted, and the uses of plants that could provide natural remedies for illness and injury, as well as material for tools and utensils. Increasingly, guides to wildflowers and other plants have begun to include in their descriptions notices of the uses to which native peoples put various species. Particularly in the Great Plains, the tribes have managed to retain much of this traditional lore and their sense of relationship to their environment, and government agencies and conservation organizations have found great benefits from cooperation with the tribes, drawing on their expert knowledge and immediate and reverent relation to the land in the effort to save and restore some viable portion of the rapidly diminishing, scattered remains of the once-vast, uninterrupted vista of prairie, the sea of grass.

For accounts of the relations of traditional native American cultures to nature, see:

We are the Land: Native American Views of Nature

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-94-017-0149-5_17

Protecting the Earth, Protecting Ourselves: Stories from Native America

https://nonprofitquarterly.org/protecting-the-earth-protecting-ourselves-stories-from-native-america

Building an American Serengeti in Montana: The perils of rewilding ranchland with ranchers still on it

https://www.sierraclub.org/sierra/2019-5-september-october/feature/building-american-serengeti-montana-american-prairie-reserve

Horsehair Bridle

https://www.audubonofkansas.org/newsletters.cfm?fx=HVVLNI2CTFSANM0Q

Water for Many

For most people, water would not be one of the first things that would come to mind in connection with grasslands. And in fact, while the average annual rainfall in the U.S.A. as a whole is 38 inches/year, the average annual rainfall in the Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve is only 30 inches in a dry year, while further west, the shortgrass prairie averages only 11 to 20 inches per year. Yet the relations between the grasslands and water are manifold and complex. Here in Kansas, in the middle of the state, we have two great wetlands, Quivira National Wildlife Refuge and Cheyenne Bottoms, both marshes of international significance recognized by both the Ramsar Convention and Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve as crucial stops and refueling sites for migratory shorebirds and waterfowl, including the endangered Whooping Crane. Cheyenne Bottoms is considered the most important shorebird migration point in the western hemisphere, attracting 45% of all migratory shorebirds nesting in North America stopover at Cheyenne Bottoms. But less dramatic water resources also dot the grasslands of central North America. Hundreds of picturesque small streams and slow-flowing rivers meander through the plains, affording an oasis for wildlife and in the days of settlement, a blessing for travelers who found watering-places few and far between. From the panhandle of Texas north through eastern Colorado and western Kansas to Nebraska, playas, or ephemeral wetlands, not only provide a unique habitat for a variety of plants and animals, but also play a crucial role in filtering groundwater and gradually restoring the aquifers. Because of their ephemeral nature, sometimes disappearing for fifteen or twenty year, then coming back with abundant rainfall, playas are easily overlooked or dismissed; many have fallen victim to the plow, or to the accumulation of sediments and chemicals from adjacent agricultural operations. Those aquifers have played an essential role in turning the western plains into productive agricultural fields; but continued over-extraction for irrigation is depleting underground reservoirs faster than rainfall and playas can recharge them, and it is only too clear that without drastic reductions in use, a day of reckoning looms when it will no longer be economically feasible to rely on their bounty. When that day comes, and even now, as it approaches, the consequences for the ecosystems of the grasslands, and the human endeavors that have flourished on their exploitation, will be disastrous.

For most people, water would not be one of the first things that would come to mind in connection with grasslands. And in fact, while the average annual rainfall in the U.S.A. as a whole is 38 inches/year, the average annual rainfall in the Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve is only 30 inches in a dry year, while further west, the shortgrass prairie averages only 11 to 20 inches per year. Yet the relations between the grasslands and water are manifold and complex. Here in Kansas, in the middle of the state, we have two great wetlands, Quivira National Wildlife Refuge and Cheyenne Bottoms, both marshes of international significance recognized by both the Ramsar Convention and Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve as crucial stops and refueling sites for migratory shorebirds and waterfowl, including the endangered Whooping Crane. Cheyenne Bottoms is considered the most important shorebird migration point in the western hemisphere, attracting 45% of all migratory shorebirds nesting in North America stopover at Cheyenne Bottoms. But less dramatic water resources also dot the grasslands of central North America. Hundreds of picturesque small streams and slow-flowing rivers meander through the plains, affording an oasis for wildlife and in the days of settlement, a blessing for travelers who found watering-places few and far between. From the panhandle of Texas north through eastern Colorado and western Kansas to Nebraska, playas, or ephemeral wetlands, not only provide a unique habitat for a variety of plants and animals, but also play a crucial role in filtering groundwater and gradually restoring the aquifers. Because of their ephemeral nature, sometimes disappearing for fifteen or twenty year, then coming back with abundant rainfall, playas are easily overlooked or dismissed; many have fallen victim to the plow, or to the accumulation of sediments and chemicals from adjacent agricultural operations. Those aquifers have played an essential role in turning the western plains into productive agricultural fields; but continued over-extraction for irrigation is depleting underground reservoirs faster than rainfall and playas can recharge them, and it is only too clear that without drastic reductions in use, a day of reckoning looms when it will no longer be economically feasible to rely on their bounty. When that day comes, and even now, as it approaches, the consequences for the ecosystems of the grasslands, and the human endeavors that have flourished on their exploitation, will be disastrous.

For more information about playas and wetlands in Kansas:

Playas: An Important Source of Water in the Great Plains

https://www.audubonofkansas.org/newsletters.cfm?fx=KKATHUN8RCWGDKV

The Value of Marshes: An Essay on Kansas Wetlands

https://www.audubonofkansas.org/newsletters.cfm?fx=LJMGVHH9GY7WTQ2P

Playas work for Kansas

https://playasworkforkansas.com

A “City Boy” and World Traveler Responds to Cheyenne Bottoms and Quivira

https://www.audubonofkansas.org/newsletters.cfm?fx=05KBRP1YIXOMTKLO

Quivira’s Unique Qualities for Wildlife and Nature-based Visitation

https://www.audubonofkansas.org/newsletters.cfm?fx=DA4AMFVQZCL8NUEM

On grasslands as sources of drinking water, see:

https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/gtr/gtr_srs039.pdf

On the importance of grasslands as purifiers and storage of water that would otherwise be lost, see:

For the problem of depletion of the aquifers, see:

Lucas Bessire, Running Out: in search of water on the high plains (Princeton University Press, 2021) xiv + 246 pp., and review in Prairie Wings 2021/2022 — https://www.audubonofkansas.org/prairie-wings.cfm?fx=3I1FA03K1Y1XVUPN

For overviews of water issues in Kansas, see:

Water in Kansas: Where We’ve Been, Where We’re Headed

Prairie Wings 2018— https://www.audubonofkansas.org/prairie-wings.cfm?fx=A48HA6400SMOUNYP

Update on Water in Kansas

Prairie Wings 2021— https://www.audubonofkansas.org/prairie-wings.cfm?fx=511ZUXO5Q7AI3CNA

The “50-Year Vision for the Future of Water in Kansas”: A Conservationist’s View

Prairie Wings 2015— https://www.audubonofkansas.org/prairie-wings.cfm?fx=QZXMYXEMYNVOO202

Review of water legislation in Kansas with a focus on a failed attempt to gut the Clean Water Act in 2019, see: https://www.audubonofkansas.org/aok-news.cfm?id=13&pg=1&cid=7

Playas in Peril, Wetlands in Jeopardy: Playas and Other Wetlands Face Their Gravest Legal Threat So Farhttps://www.audubonofkansas.org/newsletters.cfm?fx=7C9X3D2NLSYL7O7G

The Year that We Almost Lost Playas in Western Kansashttps://www.audubonofkansas.org/newsletters.cfm?fx=LG8CJTZ36QKVGP8F

For Audubon of Kansas’ efforts to save wetlands in Kansas:

AOK Hosts an Annual Celebration of Cranes at Quivira National Wildlife Refuge during the first weekend in November https://www.audubonofkansas.org/newsletters.cfm?fx=SJJ5Z70X6M16WJH7

AOK Continues Pressure on Behalf of Quivira Water Right

https://www.audubonofkansas.org/newsletters.cfm?fx=EXDCDNG5WN5R5BEY

Notice of AOK Lawsuit on behalf of Quivira Water Right

https://www.audubonofkansas.org/newsletters.cfm?fx=JQP4X6T3SOOUPXCH

and

https://www.audubonofkansas.org/aok-news.cfm?id=218

Audubon of Kansas is Working to Restore Quivira National Wildlife Refuge’s Water Rightshttps://www.audubonofkansas.org/newsletters.cfm?fx=QHCFH4SCS46R16RM

Jan Garton and the Campaign to Save Cheyenne Bottoms

https://www.audubonofkansas.org/prairie-wings.cfm?fx=OT4ITDPCHF5B0IVN

Saving Cheyenne Bottoms – Part Two

https://www.audubonofkansas.org/prairie-wings.cfm?fx=HP5M7BMX2E6Q3RWG

Grasslands are Good for the Herd — and Birds!

Healthy grasslands not only produce healthy cattle, they also support a wide diversity of plants and insects that grassland birds need to thrive. Prescribed fire is an important component of maintaining a healthy prairie. People unfamiliar with prairies—in either their natural or their managed state—often regard prairie fires with concern, if not alarm. In fact, periodic fires, either caused by lightning strikes or deliberately set by the native peoples in their hunting and food-gathering endeavors, were a feature of life on the great prairies of the plains before the Europeans came. Prairies need periodic fires to stay healthy—and to stay prairie! Without burning, thatch accumulates, retarding new growth, and invasive plants—trees like Eastern Red Cedar, shrubs like Rough-Leaved Dogwood and Plum thickets—will take over and transform the prairie. Red Cedar can turn a diverse community of dozens of grasses and forbs into a relatively sterile monoculture. Encroachment of trees and shrub thickets makes for less desirable pasturage for livestock. Periodic burning stimulates new growth: given the choice, cattle will always gravitate to graze the succulent, tender new green shoots that spring up shortly after burning. However, burning every year encourages non-native warm season grasses that replace native warm-season grasses and forbs on which many native useful insects, butterflies and other pollinators, depend. Moreover, the native warm-season grasses, once established, require less management and fertilizer, and are more drought-resistant. Burning every three years constitutes an ideal regimen for livestock; in addition, burning every three years, or better yet, burning one-third of a given prairie in rotation each year for three years provides good grazing and favors ground-nesting grassland birds like prairie-chickens, meadowlarks, curlews, and grassland passerines, by leaving them adequate nesting cover for protection from predators.

Healthy grasslands not only produce healthy cattle, they also support a wide diversity of plants and insects that grassland birds need to thrive. Prescribed fire is an important component of maintaining a healthy prairie. People unfamiliar with prairies—in either their natural or their managed state—often regard prairie fires with concern, if not alarm. In fact, periodic fires, either caused by lightning strikes or deliberately set by the native peoples in their hunting and food-gathering endeavors, were a feature of life on the great prairies of the plains before the Europeans came. Prairies need periodic fires to stay healthy—and to stay prairie! Without burning, thatch accumulates, retarding new growth, and invasive plants—trees like Eastern Red Cedar, shrubs like Rough-Leaved Dogwood and Plum thickets—will take over and transform the prairie. Red Cedar can turn a diverse community of dozens of grasses and forbs into a relatively sterile monoculture. Encroachment of trees and shrub thickets makes for less desirable pasturage for livestock. Periodic burning stimulates new growth: given the choice, cattle will always gravitate to graze the succulent, tender new green shoots that spring up shortly after burning. However, burning every year encourages non-native warm season grasses that replace native warm-season grasses and forbs on which many native useful insects, butterflies and other pollinators, depend. Moreover, the native warm-season grasses, once established, require less management and fertilizer, and are more drought-resistant. Burning every three years constitutes an ideal regimen for livestock; in addition, burning every three years, or better yet, burning one-third of a given prairie in rotation each year for three years provides good grazing and favors ground-nesting grassland birds like prairie-chickens, meadowlarks, curlews, and grassland passerines, by leaving them adequate nesting cover for protection from predators.

On burning regimen, see

Potential Benefits of Patch Burning for Prairie-Chickens, see in Prairie Wings Winter 2016-Spring 2017:

https://www.audubonofkansas.org/newsletters.cfm?fx=JG5AH0XZQJBF9FUQ

Prairie Burning Practices as a Factor in the Demise of the Prairie-Chicken see in Prairie Wings Winter 2012-Spring 2013:

https://www.audubonofkansas.org/prairie-wings.cfm?fx=8NP1MTL4WJDB9GPY

The Science of Prairie Burning

https://www.illinoisscience.org/2019/09/the-science-of-prairie-burning/

Prairie Burns: Protecting Precious Habitat with Fire

https://www.threeriversparks.org/blog/prairie-burns-protecting-precious-habitat-fire

The Best Time to Burn

https://prairieecologist.com/2015/04/22/whats-the-best-time-to-burn/

On invasive Old World Bluestems, see in Prairie Wings 2018:

https://www.audubonofkansas.org/prairie-wings.cfm?fx=LIS1S2GZHB8BUI4P

On burning and grassland birds, see:

Grassland Birds

https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/nrcs144p2_054067.pdf

Fire in the Tallgrass Prairie: Finding the Right Balance of Burning for Birds

https://www.suttoncenter.org/wp-content/uploads/pdfs/publications/2006 Reinking Birding.pdf

Restoring Nebraska’s Prairie Grasslands with Prescribed Burning

https://wildlifemanagement.institute/outdoor-news-bulletin/january-2022/restoring-nebraskas-prairie-grasslands-prescribed-burning

Grasslands are an Abundant Source of Food

Have you seen the signs along Kansas highways that proclaim “One Kansas Farmer Feeds 155 people and YOU!” It is true that Kansas farmers produce a lot of food. However, this statistic is true only if people were vegetarian. If only meat was consumed, this number would be closer to 16 people per farmer (see 10% rule in ecology). Compared to the 1900s, today are fewer producers (farmers and ranchers) producing much more food. In 1900, 41% of the American workforce was employed in agriculture compared to 1.9% in 2020. Even though there are fewer farmers, more food is being produced. Increases in yields and quality have resulted from advances in plant and animal breeding, more efficient farming practices, and the rapid development of inexpensive chemical fertilizers and pesticides. Farm operations have become increasingly specialized as well from an average of about five commodities per farm in 1900 to about one per farm in 2000. (Source of data in this paragraph can be found here.)

Have you seen the signs along Kansas highways that proclaim “One Kansas Farmer Feeds 155 people and YOU!” It is true that Kansas farmers produce a lot of food. However, this statistic is true only if people were vegetarian. If only meat was consumed, this number would be closer to 16 people per farmer (see 10% rule in ecology). Compared to the 1900s, today are fewer producers (farmers and ranchers) producing much more food. In 1900, 41% of the American workforce was employed in agriculture compared to 1.9% in 2020. Even though there are fewer farmers, more food is being produced. Increases in yields and quality have resulted from advances in plant and animal breeding, more efficient farming practices, and the rapid development of inexpensive chemical fertilizers and pesticides. Farm operations have become increasingly specialized as well from an average of about five commodities per farm in 1900 to about one per farm in 2000. (Source of data in this paragraph can be found here.)

The conversion of prairie to agricultural development has played a major role in the so-called “Green Revolution” that promised an end to world hunger, despite the accelerating growth of human populations. But the cost of that development, and its limits, are only now beginning to be calculated. The loss of native grassland— approximately 47% in the Great Plains —threatens the existence of many species, and means the extinction of some, never to return; it means also the loss of one of the most efficient carbon sinks in nature, combatting global climate change (we will talk about how soil conserves carbon in a later installment). Moreover, not all farming and ranching practices can be sustained over the long term. Over-grazing degrades native grasses, opening the way to invasive species that are unsuitable sustenance for cattle or sheep, degrading the ability of the land to retain rainwater, and accelerating run-off that pollutes the water supply. Over-extraction of water from rivers and streams impacted by drought and excessive reliance on ancient aquifers for irrigation means that these conventional water sources are becoming harder to utilize as underground water tables drop and some may even run dry in a matter of a few decades in Kansas. Buildup of chemical fertilizers, herbicides, and pesticides poisons the soil and rivers, eventually eroding the land’s productivity; run-off degrades our water supply. The concentration of food-processing operations in the hands of a few monopolistic large corporations raises costs for the consumer and gradually squeezes out the family farmer. Clearly another “Green Revolution” in sustainable agriculture is needed, and pioneering work on the promise of sustainable agriculture is being pursued in Kansas.

For a summary of the threats to grasslands, see

A rancher’s view of the destruction of the native grasslands of the Sand Hills: https://www.audubonofkansas.org/prairie-wings.cfm?fx=YCGT4XSWJ6AZ7MEP

America’s Native Grasslands are Disappearing: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/nov/05/americas-native-grasslands-disappearing

Understanding Grassland Loss in the Northern Great Plains: https://www.worldwildlife.org/magazine/issues/winter-2018/articles/understanding-grassland-loss-in-the-northern-great-plains

For a general treatment of problems created by the dominant agribusiness model of our culture, see Michael Pollan’s 2009 New York Times best-seller, The Omnivore’s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals, and its critics.

Agricultural practices that preserve grasslands

On grassland bird habitat requirements and management practices for landowners, see: https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/nrcs144p2_054067.pdf

The Land Institute: https://landinstitute.org/ and these videos from The Land Institute:

https://landinstitute.org/video-audio/land-people-proper-economy

https://landinstitute.org/video-audio/the-land-institute-civic-science-programming-lunch-learn

For an example of the efforts of ranchers to regenerate Kansas grazing land with attention to wildlife habitat, scenic beauty, recreation and tourism, see: https://www.kglc.org/kglc-kansas-prairie-primer.cfm

See also the chapter "How Will We Feed Ourselves?" in Janine Benyus's book, Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature (New York: Perennial Books, 1997, 2002)

Audubon of Kansas supporting environmentally-friendly farming:

For an Audubon of Kansas Board Member’s discussion about changes in farming:https://www.audubonofkansas.org/newsletters.cfm?fx=Z1BHNSZVL4JVBJIG

Connie Achterberg’s Wildlife-Friendly Demonstration Farm

https://www.audubonofkansas.org/prairie-wings.cfm?fx=6USGAC89SDWQYMC0

The 2018 Federal Farm Bill: The Changing Face of American Agriculture https://www.audubonofkansas.org/prairie-wings.cfm?fx=Z1BHNSZVL4JVBJIG

The 2018 Farm Bill: I Live in Town, Why Should I Care?

https://www.audubonofkansas.org/prairie-wings.cfm?fx=OS7AD3GZ8G9NF99W

Envisioning and Enacting a 50-Year Farm Bill

https://www.audubonofkansas.org/prairie-wings.cfm?fx=MQU8AW6QFTNIBPGZ

Grasslands are Places to Enjoy

For a selection of sites to visit to sample the range of natural experiences in Kansas, see:

For a treatment of how AOK views the natural world contrasted with the dominant utilitarian attitudes of our society, see: “Thinking about Nature”

For an example of the spiritual and aesthetic values carried by grasslands, see: “Prairie Song”.

About Audubon of Kansas

Audubon of Kansas (AOK) is a regional grassroots organization serving as an umbrella resource for several local chapters. AOK promotes the enjoyment, understanding, protection, and restoration of natural ecosystems in the Great Plains. It is not administered or funded by the National Audubon Society. Its activities include: 1) education of the public through presentations, social media, outreach, monthly email newsletters, and the publication of Prairie Wings magazine; 2) conservation of sanctuaries in Kansas and Nebraska where the public can experience typical regional environments through visits and trails, and where ecologically sound farming and ranching techniques can be demonstrated; and 3) advocacy on issues ranging from the preservation of endangered species, the control of non-native invasive plants and animals, preserving clean air and water, and saving our heritage of prairies and wetlands.